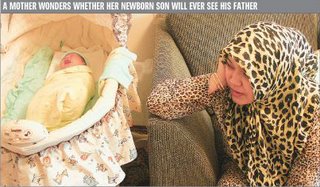

A MOTHER WONDERS WHETHER HER NEWBORN SON WILL EVER SEE HIS FATHER

SCOTT ROBERTS

A day after giving birth, Kamila Telendibaeva sat alone in the corner of a cold hospital room gazing at her newborn son.

Bound tightly in a white blanket, the infant slept soundly as his mother chewed on the nail of her index finger.

"He's got his daddy's eyes," Ms. Telendibaeva said, clad in a blue housecoat and a leopard-print veil. "It makes me think of him, and it's hard."

This was the fourth time the 29-year-old had given birth, but the first time she did it alone, without her husband by her side.

For more than two months, Huseyin Celil (pronounced je-lil) has sat in a Chinese jail cell facing charges for alleged involvement in separatist activities supposedly dating back to the early 1990s, when he lived in the country's far-western Xinjiang region.

In March, the Canadian citizen was arrested in Uzbekistan while visiting his wife's family. Three months later, he was extradited to China, accused of terrorist activities and killing a Chinese government official in Kyrgyzstan in March of 2000.

His family and his lawyer vehemently deny the allegations, saying Mr. Celil was in Turkey waiting for refugee status in 2000. His wife admits he was politically active in his homeland and had spoken out against China, but says he had never been violent and is certainly not a terrorist.

But they likely won't get a chance to defend him. Chinese officials are keeping Mr. Celil's whereabouts secret, saying only that his trial is not yet complete. China has denied the Canadian government consular access to him, which contradicts the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations.

The ordeal has taken its toll on the Burlington, Ont., family.

With the birth of the baby, who will be one week old tomorrow, Ms. Telendibaeva now has four sons and raising them is a full-time job. Her eldest, seven-year-old Mohammad, is developmentally disabled and uses a wheelchair. He cannot bathe himself or eat without assistance. Ms. Telendibaeva's mother has flown to Canada on a six-month visa to help.

With no breadwinner, finances are quickly drying up. The family survives on $600 a month in welfare payments. Amid the chaos of single parenthood, Ms. Telendibaeva says she is always thinking about her husband, constantly wondering where he is, how he is and if he's ever coming home.

The Department of Foreign Affairs maintains it is actively working to find out where Mr. Celil is being held and precisely what charges he's facing, and to ensure he has adequate representation.

So far, diplomatic efforts have gotten nowhere. Foreign Affairs Minister Peter MacKay raised Mr. Celil's case during a meeting last month with his Chinese counterpart. But the minister was brushed off, receiving no information about the Canadian in custody.

Wayne Marston, NDP critic for international affairs, is slamming the government for not doing enough. He's calling on Prime Minister Stephen Harper to personally get involved in the case and send a special envoy to China in search of answers.

"I can't fathom why Mr. Harper wouldn't come to the aid of a Canadian citizen," said Mr. Marston, MP for Hamilton East-Stoney Creek. "It's baffling to me. We have a Canadian citizen here who is under the threat of death. What further extreme do you need to pull out all the stops to try to help?"

Before his detainment, Mr. Celil was an imam at a Hamilton mosque. He was a popular mentor to young pupils and was studying accounting at Mohawk College, his wife said.

Three weeks ago, the family thought they had struck a lead in the case when Mr. Celil's sister in China was told by a local police officer that her brother was being held in either Kashgar or Urumqi, cities in Xinjiang region. But Canadian officials have been unable to confirm the rumour.

Chinese officials told Ottawa this month they are not seeking the death penalty, although the country has sentenced Mr. Celil to death once before. In 1994, he was arrested in China on charges of forming a political party to work on behalf of the Uyghur people, a Muslim, Turkic-language minority group long at odds with China over the right to greater freedom.

After serving a month in prison, Mr. Celil escaped, eventually buying false documents to enter Uzbekistan, his wife said. He made his way to Turkey before being granted refugee status in Canada in 2001. Meanwhile, in China, a court sentenced Mr. Celil to death in absentia for his alleged role in the anti-government political movement.

The family's lawyer said he worries more about Mr. Celil's condition with each passing day.

"My private fear is that he's not in the shape to be seen and that's why they're denying access to him," said Chris MacLeod, alluding to the possibility of torture.

More than a month ago, Mr. MacLeod wrote a letter to the Chinese ambassador to Canada, requesting a visa so he could visit his client in jail. There has been no response.

Government officials in Canada have also been tight-lipped on the case, rarely commenting publicly and often having little to say.

"The minister is following this case very closely," said Foreign Affairs spokesperson Ambra Dickie. "We continue to maintain regular contact with Mr. Celil's family in Canada. The minister, Mr. MacKay, has personally met with his wife."

But that was more than four months ago, when Mr. Celil was being held in Uzbekistan. "I met with [Mr. MacKay] for 15 minutes and he said he would do everything he could to get him out," Ms. Telendibaeva said.

"He told me they would try to get Russia to put pressure on China. But he did not do enough."

Charles Burton, a former Canadian diplomat based in China, believes Canada is steadily losing negotiating power as time drags on.

"The whole case hasn't been handled very well and I'm very concerned about Mr. Celil," said Mr. Burton, a professor of political science at Ontario's Brock University. "In the Chinese system, once someone comes up for trial it's very unusual for them to be declared not guilty. If he is found guilty, the question is what the nature of the punishment will be."

Mr. Burton said China has used the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks to crack down on the Uyghur minority, aiming to convince the international community that the group promotes terrorism.

"Since 9/11 there are blurred lines between what's considered political activity, what's separatism and the Chinese government calls terrorism," he said. "The Chinese government wants the West to believe Uyghurs are terrorists. But there is no empirical evidence of this."

If Ms. Telendibaeva could get one message to her husband it would be that he has another son, and that the baby is named Zubeyir, the name he liked. Family friends suggested she name the child after his father, but Ms. Telendibaeva refused.

"I won't do that. I don't want to replace him because I still have hope that he's coming home," she said defiantly.

But as weeks turn into months without word on his condition, she cannot help but lose some of that hope as the reality of the situation sets in. She may never see her husband again. He may never see his child. And she knows that.

Article Source

1 comment:

epchil yasiliptu.

asta asta tehimu jiq uchurlar toplansa paydiliq bir menbe bolup qalghusi.

Post a Comment