A meeting of civilisations: The mystery of China's celtic mummies

The discovery of European corpses thousands of miles away suggests a hitherto unknown connection between East and West in the Bronze Age.

Clifford Coonan reports from Urumqi

Published: 28 August 2006

Solid as a warrior of the Caledonii tribe, the man's hair is reddish brown flecked with grey, framing high cheekbones, a long nose, full lips and a ginger beard. When he lived three thousand years ago, he stood six feet tall, and was buried wearing a red twill tunic and tartan leggings. He looks like a Bronze Age European. In fact, he's every inch a Celt. Even his DNA says so.

But this is no early Celt from central Scotland. This is the mummified corpse of Cherchen Man, unearthed from the scorched sands of the Taklamakan Desert in the far-flung region of Xinjiang in western China, and now housed in a new museum in the provincial capital of Urumqi. In the language spoken by the local Uighur people in Xinjiang, "Taklamakan" means: "You come in and never come out."

The extraordinary thing is that Cherchen Man was found - with the mummies of three women and a baby - in a burial site thousands of miles to the east of where the Celts established their biggest settlements in France and the British Isles.

DNA testing confirms that he and hundreds of other mummies found in Xinjiang's Tarim Basin are of European origin. We don't know how he got there, what brought him there, or how long he and his kind lived there for. But, as the desert's name suggests, it is certain that he never came out.

His discovery provides an unexpected connection between east and west and some valuable clues to early European history.

One of the women who shared a tomb with Cherchen Man has light brown hair which looks as if it was brushed and braided for her funeral only yesterday. Her face is painted with curling designs, and her striking red burial gown has lost none of its lustre during the three millenniums that this tall, fine-featured woman has been lying beneath the sand of the Northern Silk Road.

The bodies are far better preserved than the Egyptian mummies, and it is sad to see the infants on display; to see how the baby was wrapped in a beautiful brown cloth tied with red and blue cord, then a blue stone placed on each eye. Beside it was a baby's milk bottle with a teat, made from a sheep's udder.

Based on the mummy, the museum has reconstructed what Cherchen Man would have looked like and how he lived. The similarities to the traditional Bronze Age Celts are uncanny, and analysis has shown that the weave of the cloth is the same as that of those found on the bodies of salt miners in Austria from 1300BC.

The burial sites of Cherchen Man and his fellow people were marked with stone structures that look like dolmens from Britain, ringed by round-faced, Celtic figures, or standing stones. Among their icons were figures reminiscent of the sheela-na-gigs, wild females who flaunted their bodies and can still be found in mediaeval churches in Britain. A female mummy wears a long, conical hat which has to be a witch or a wizard's hat. Or a druid's, perhaps? The wooden combs they used to fan their tresses are familiar to students of ancient Celtic art.

At their peak, around 300BC, the influence of the Celts stretched from Ireland in the west to the south of Spain and across to Italy's Po Valley, and probably extended to parts of Poland and Ukraine and the central plain of Turkey in the east. These mummies seem to suggest, however, that the Celts penetrated well into central Asia, nearly making it as far as Tibet.

The Celts gradually infiltrated Britain between about 500 and 100BC. There was probably never anything like an organised Celtic invasion: they arrived at different times, and are considered a group of peoples loosely connected by similar language, religion, and cultural expression.

The eastern Celts spoke a now-dead language called Tocharian, which is related to Celtic languages and part of the Indo-European group. They seem to have been a peaceful folk, as there are few weapons among the Cherchen find and there is little evidence of a caste system.

Even older than the Cherchen find is that of the 4,000-year-old Loulan Beauty, who has long flowing fair hair and is one of a number of mummies discovered near the town of Loulan. One of these mummies was an eight-year-old child wrapped in a piece of patterned wool cloth, closed with bone pegs.

The Loulan Beauty's features are Nordic. She was 45 when she died, and was buried with a basket of food for the next life, including domesticated wheat, combs and a feather.

The Taklamakan desert has given up hundreds of desiccated corpses in the past 25 years, and archaeologists say the discoveries in the Tarim Basin are some of the most significant finds in the past quarter of a century.

"From around 1800BC, the earliest mummies in the Tarim Basin were exclusively Caucausoid, or Europoid," says Professor Victor Mair of Pennsylvania University, who has been captivated by the mummies since he spotted them partially obscured in a back room in the old museum in 1988. "He looked like my brother Dave sleeping there, and that's what really got me. Lying there with his eyes closed," Professor Mair said.

It's a subject that exercises him and he has gone to extraordinary lengths, dodging difficult political issues, to gain further knowledge of these remarkable people.

East Asian migrants arrived in the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin about 3,000 years ago, Professor Mair says, while the Uighur peoples arrived after the collapse of the Orkon Uighur Kingdom, based in modern-day Mongolia, around the year 842.

A believer in the "inter-relatedness of all human communities", Professor Mair resists attempts to impose a theory of a single people arriving in Xinjiang, and believes rather that the early Europeans headed in different directions, some travelling west to become the Celts in Britain and Ireland, others taking a northern route to become the Germanic tribes, and then another offshoot heading east and ending up in Xinjiang.

This section of the ancient Silk Road is one of the world's most barren precincts. You are further away from the sea here than at any other place, and you can feel it. This where China tests its nuclear weapons. Labour camps are scattered all around - who would try to escape? But the remoteness has worked to the archaeologists' advantage. The ancient corpses have avoided decay because the Tarim Basin is so dry, with alkaline soils. Scientists have been able to glean information about many aspects of our Bronze Age forebears from the mummies, from their physical make-up to information about how they buried their dead, what tools they used and what clothes they wore.

In her book The Mummies of Urumchi, the textile expert Elizabeth Wayland Barber examines the tartan-style cloth, and reckons it can be traced back to Anatolia and the Caucasus, the steppe area north of the Black Sea. Her theory is that this group divided, starting in the Caucasus and then splitting, one group going west and another east.

Even though they have been dead for thousands of years, every perfectly preserved fibre of the mummies' make-up has been relentlessly politicised.

The received wisdom in China says that two hundred years before the birth of Christ, China's emperor Wu Di sent an ambassador to the west to establish an alliance against the marauding Huns, then based in Mongolia. The route across Asia that the emissary, Zhang Qian, took eventually became the Silk Road to Europe. Hundreds of years later Marco Polo came, and the opening up of China began.

The very thought that Caucasians were settled in a part of China thousands of years before Wu Di's early contacts with the west and Marco Polo's travels has enormous political ramifications. And that these Europeans should have been in restive Xinjiang hundreds of years before East Asians is explosive.

The Chinese historian Ji Xianlin, writing a preface to Ancient Corpses of Xinjiang by the Chinese archaeologist Wang Binghua, translated by Professor Mair, says China "supported and admired" research by foreign experts into the mummies. "However, within China a small group of ethnic separatists have taken advantage of this opportunity to stir up trouble and are acting like buffoons. Some of them have even styled themselves the descendants of these ancient 'white people' with the aim of dividing the motherland. But these perverse acts will not succeed," Ji wrote.

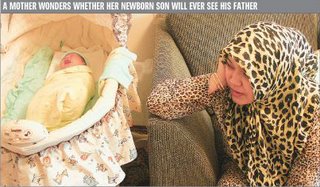

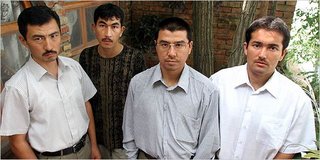

Many Uighurs consider the Han Chinese as invaders. The territory was annexed by China in 1955, and the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region established, and there have been numerous incidents of unrest over the years. In 1997 in the northern city of Yining there were riots by Muslim separatists and Chinese security forces cracked down, with nine deaths. There are occasional outbursts, and the region remains very heavily policed.

Not surprisingly, the government has been slow to publicise these valuable historical finds for fear of fuelling separatist currents in Xinjiang.

The Loulan Beauty, for example, was claimed by the Uighurs as their symbol in song and image, although genetic testing now shows that she was in fact European.

Professor Mair acknowledges that the political dimension to all this has made his work difficult, but says that the research shows that the people of Xinjiang are a dizzying mixture. "They tend to mix as you enter the Han Dynasty. By that time the East Asian component is very noticeable," he says. "Modern DNA and ancient DNA show that Uighurs, Kazaks, Kyrgyzs, the peoples of central Asia are all mixed Caucasian and East Asian. The modern and ancient DNA tell the same story," he says.

Altogether there are 400 mummies in various degrees of desiccation and decomposition, including the prominent Han Chinese warrior Zhang Xiong and other Uighur mummies, and thousands of skulls. The mummies will keep the scientists busy for a long time. Only a handful of the better-preserved ones are on display in the impressive new Xinjiang museum. Work began in 1999, but was stopped in 2002 after a corruption scandal and the jailing of a former director for involvement in the theft of antiques.

The museum finally opened on the 50th anniversary of China's annexation of the restive region, and the mummies are housed in glass display cases (which were sealed with what looked like Sellotape) in a multi-media wing.

In the same room are the much more recent Han mummies - equally interesting, but rendering the display confusing, as it groups all the mummies closely together. Which makes sound political sense.

This political correctness continues in another section of the museum dedicated to the achievements of the Chinese revolution, and boasts artefacts from the Anti-Japanese War (1931-1945).

Best preserved of all the corpses is Yingpan Man, known as the Handsome Man, a 2,000-year-old Caucasian mummy discovered in 1995. He had a gold foil death mask - a Greek tradition - covering his blond, bearded face, and wore elaborate golden embroidered red and maroon wool garments with images of fighting Greeks or Romans.

The hemp mask is painted with a soft smile and the thin moustache of a dandy. Currently on display at a museum in Tokyo, the handsome Yingpan man was two metres tall (six feet six inches), and pushing 30 when he died. His head rests on a pillow in the shape of a crowing cockerel.

Article Sources